What's all this hubbub and yelling,

Commotion and scamper of feet,

With ear-splitting clatter of kettles and cans,

Wild laughter down Mafeking Street?

O, those are the kids whom we fought for

(You might think they'd been scoffing our rum)

With flags that they waved when we marched off to war

In the rapture of bugle and drum.

Now they'll hang Kaiser Bill from a lamp-post,

Von Tirpitz they'll hang from a tree....

We've been promised a 'Land Fit for Heroes'---

What heroes we heroes must be!

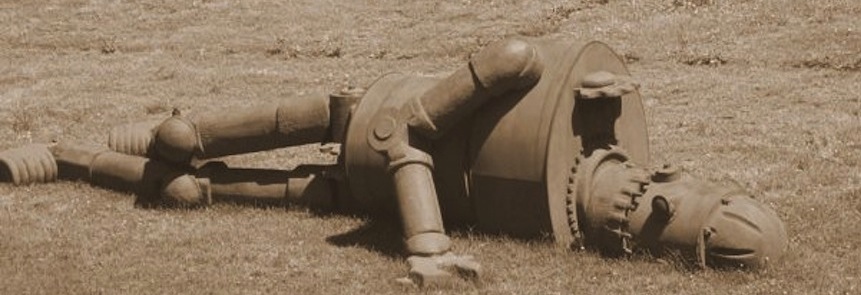

And the guns that we took from the Fritzes,

That we paid for with rivers of blood,

Look, they're hauling them down to Old Battersea Bridge

Where they'll topple them, souse, in the mud!

But there's old men and women in corners

With tears falling fast on their cheeks,

There's the armless and legless and sightless---

It's seldom that one of them speaks.

And there's flappers gone drunk and indecent

Their skirts kilted up to the thigh,

The constables lifting no hand in reproof

And the chaplain averting his eye....

When the days of rejoicing are over,

When the flags are stowed safely away,

They will dream of another wild 'War to End Wars'

And another wild Armistice day.

But the boys who were killed in the trenches,

Who fought with no rage and no rant,

We left them stretched out on their pallets of mud

Low down with the worm and the ant.